Started a Company. Didn't Work

A few months ago, I tried to start a company. The goal was to disrupt an industry I either liked or knew a bit about. I landed on HR. Entrepreneurs solve problems - regardless of industry or experience.

I decided to blog about it because I believe my life is an open book, and what I write here is for the future.

Early Start

There was a friend I always liked talking to about startups. He was always reading and observing the space. I remember we used to meet biweekly just to discuss random ideas and thoughts we'd come across. It was great. We'd challenge each other and try to get closer to the next big thing.

But at some point, I realized that if we kept doing that, we'd never get to experience the sweetness or bitterness of any idea. Simply because we never actually tried them.

So I picked one.

I decided to go with HR - an industry I'd been watching for a while. I thought, if we take AI and embed it into HR, you could vertically dominate the entire stack.

That weekend, I built a small MVP. No backend. Just a basic frontend to show what I had in mind. It helped me explain the idea clearly to anyone I spoke to. I'd tell people, "We're the Harvey of HR." That was probably one of the first mistakes I made. I'll get into why later.

I pitched the scrappy MVP to my friend, and he liked it on the spot. I made him a cofounder. We didn't really know how to split responsibilities, but it was clear I'd be the CEO. What matters in any startup is who's leading it - because that person sets the vision and pushes it forward.

I've always asked people who run billion-dollar companies one question I'm still obsessed with:

How do you keep your learning curve ahead of your company's?

The answer is counterintuitive. Just keep running the company, and talk to as many people as you can - as different from you as possible, and stay consistent.

Back to the story. After having a mission and a barely working MVP, it was time to buy a domain and design a logo.

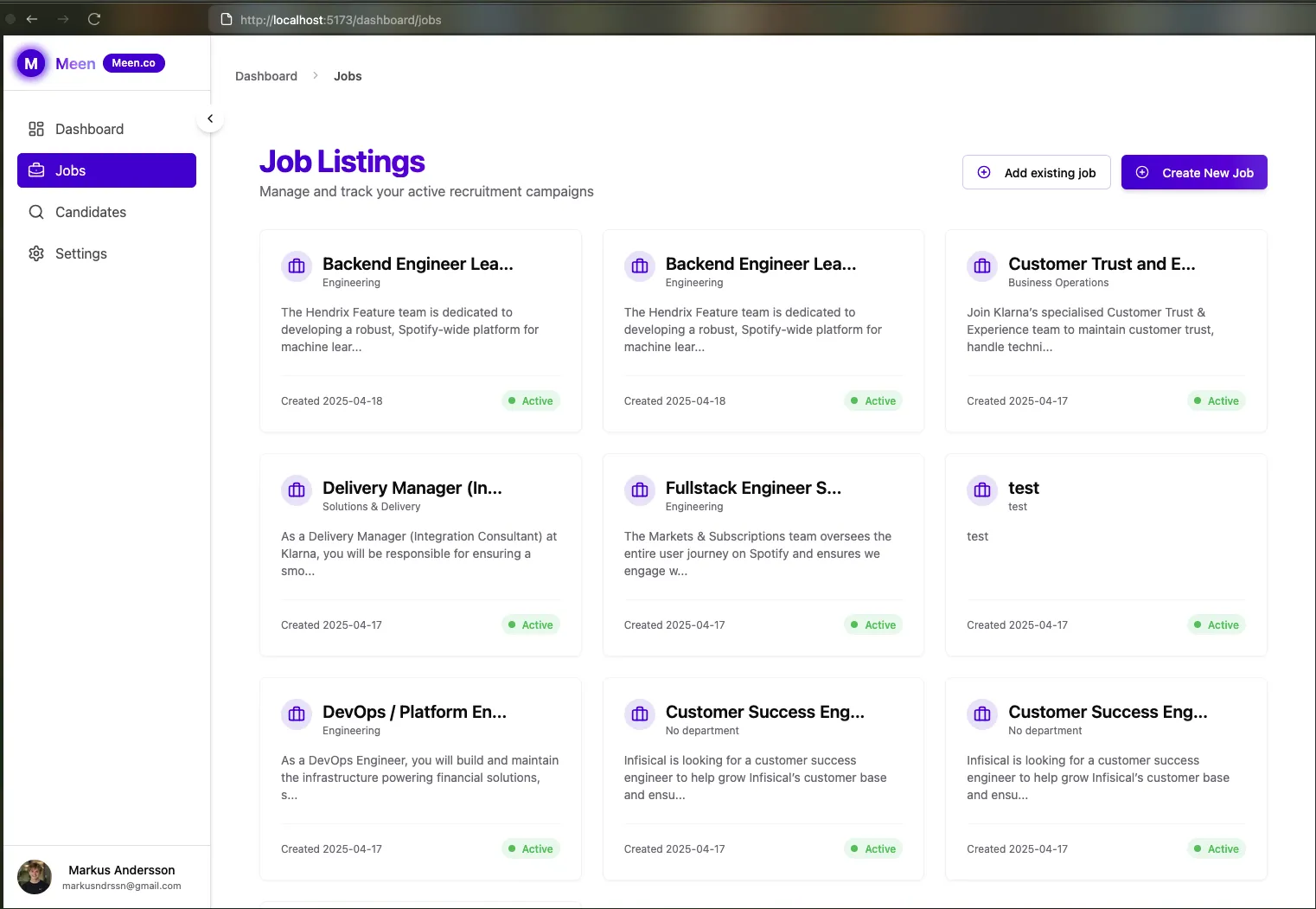

I always dreamt of having a four-letter startup name, and I made that happen with Meen.co. Meen comes from the Arabic word for "who," which ties directly to our mission - to help you hire the best people. I still think it was a smart name. The company didn't work out, but I get to keep the name, and I'm proud of that.

Rebuilding It for Growth

I always said on Twitter that the day I start a company, I'd add a day counter to track how fast we're moving and make sure the pace stays insane. And that's exactly what I did.

Initially, I tried to build an MVP with my cofounder with Cursor - We're both PMs, and but we're not technical enough to get something as an AI product to life, without an external help. At that moment at clicked that we need a technical co-founder, someone who's strong and can eventually steer the company's product development, while still maintaining a strategic view of where the company is heading - Heads up, most people suck at this, even cracked engineers.

I wanted someone truly worth it. Someone I'd trust for the next 10 years if the company actually worked. That mindset led me back to YC Co-founder Matching. I had used it a few years ago, and this felt like the right time to try again.

At the same time, I was meeting a lot of people in Saudi. I made it a point to meet people from different backgrounds - researchers, eccentric engineers, the kind of people you don't usually find in traditional hiring funnels. But there was a pattern. Most of them were inversely uncommitted. That's what pushed me to go back to YC.

If you want to build something big, you can't do it on the side. It's either all-in or all-out. That's one of my biggest principles in life. Success comes from aggressiveness, commitment, and intensity.

These are the same traits I look for in a cofounder. I believe most successful people either combine all three, or have one that's so strong it carries the rest.

Going back to YC Co-founder Matching

I was too desperate to find someone as intense/committed as me - someone with the same traits, who, despite their current situation, was hungry to build the next big thing. At that point, I decided it was the right time to get back on YC Co-founder Matching and change my location to the UK. Europe has strong talent, but not enough great companies to absorb it. Tremendous raw talent. Exactly what I was looking for.

I sent a message to a few people I liked. My criteria was straightforward: they either had to be a cracked engineer—someone who could arguably build Google in a few months—or someone with the ability to learn fast, what I like to call slope over intercept.

I met a couple of people. One guy stood out. I liked him a lot. He was a builder at heart, just wanted to build. He had that spark, that glossiness I hadn't seen in others. After a few calls, I asked him to join me. He had both - the slope and the rack.

Looking back, I probably should've taken more time to really get to know him. When people come together just to build a company and nothing more, it usually doesn't work like it should.

Building The Company again

Okay, we now had a team that could execute, a clear vision, and one mission: to build the ultimate AI headhunter.

But then came the hard part. What should the MVP look like? What's the go-to-market strategy? What do we build first? The questions kept piling up. One thing I kept hearing from other entrepreneurs was this: running a company is endlessly uncertain. You always feel behind. There's always something you didn't have time to figure out.

The idea was simple. Let's build an MVP where you fill in some info about the job role using a workflow. That workflow gets converted into a vector embedding. Then we use LinkedIn curlers and a few other tools to pull candidate profiles.

We thought LinkedIn Recruiter sucked. I still do. It's ripe for disruption. LinkedIn is one of the longest-standing incumbents that hasn't changed. No active founder. No real innovation. People use LinkedIn out of necessity, not love. And yet, it's incredibly profitable from its SaaS tools—Premium, Recruiter, Navigator.

We got a working product in just four days. We lived by the day count - it was the only way we measured time. I remember thinking: this guy might be the best engineer I've ever worked with.

The UI looked solid, even if not perfect. With Cursor's help, we shipped something fast. And that was the goal.

Now that we had a working product, it was time to reach out to as many people as possible and see how the market would react. This is a defining moment for any company - either you've built something people want, or something they don't need at all. In both cases, you end up back at the drawing board, trying to incorporate feedback.

I started sending endless emails and LinkedIn messages to everyone in my network, just to get them to try the product. I talked to a lot of HR people to understand their pain points and keep asking the questions I always ask - how, why, and what's next.

Our first lead was a cool Series A YC company. They helped us realize all the things we were doing wrong. We tried hard to convince them to be our first customer, but it took a lot of back and forth. That's B2B sales - It takes forever to close.

At the same time, we started applying to a few incubators, including YC. We made it to the final round with one of them.

That's when everything came crashing down.

The Crash Down

Every failed startup carries dreams that never came true. Things left incomplete. Ideas abandoned on the whiteboard. I think failed companies are like abandoned houses - full of stories, unfinished thoughts, and meaning that still lingers.

The crash happened when my technical cofounder got an offer from a company that gave him something undeniable. And just like that, our house was left behind.

I learned a lot from the experience. A company's trajectory—especially when it's default dead—can change at any moment.

In our case, I think it came down to priorities. We both brought different things to the table, and when that happens, alignment matters more than energy. People should choose what's best for themselves—not based on emotion or loyalty, but what actually moves their life forward.

Putting your own interests first isn't selfish. It's how life works.

What I Learned

I'm trying to quantify my learnings—regardless of how messy the situationship was.

- Startups are a game of probability. Everything matters—people, timing, place, early credentials. It's all circumstantial. But the more you try, the more the odds bend your way.

- A company is people. Not the other way around. A company is just a reflection of the people building it—how aggressive, intense, and committed they are.

- Funding isn't hard. We didn't raise, but we got close. Either through a small friends and family round or by joining an incubator.

- Get comfortable being uncomfortable. It's painful. There are ups and downs. But the ups make you forget the downs.

These are my learnings. I'm sharing them to mark this moment and make sense of the journey.

I believe life's a loop, not a destination. I'll keep throwing the dice. I'm still 19. I've got 51 years until retirement.

Until next time - I'll be out in the world.

Talking to people. Reading.

And obsessively watching what's next.